Recently, I was looking at some research papers on the join reorderability. To start with, let’s understand what do we mean by “join reorderability” and why it is important.

Background Knowledge

Here, we are looking at a query optimization problem, specifically join optimization. As mentioned by Benjamin Nevarez, there are two factors in join optimization: selection of a join order and choice of a join algorithm.

As stated by Tan Kian Lee’s lecture notes, common join algorithms include iteration-based nested loop join (tuple-based, page-based, block-based), sort-based merge join and partition-based hash join. We should consider a few factors when deciding which algorithm to use: 1) types of the join predicate (equality predicate v.s. non-equality predicate); 2) sizes of the left v.s. right join operand; 3) available buffer space & access methods.

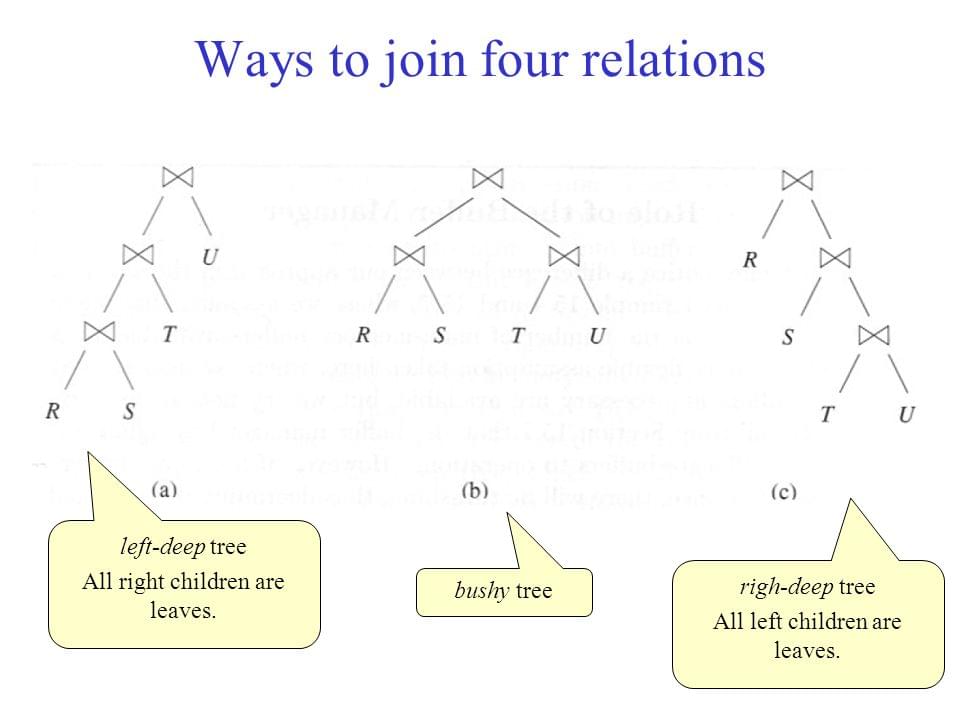

For a query attempting to join n tables together, we need n - 1 individual joins. Apart from the join algorithm applied to each join, we have to decide in which order these n tables should be joined. We could represent such join queries on multiple tables as a tree. The tree could have different shapes, such as left-deep tree, right-deep tree and bushy tree. The 3 types of trees are compared below on an example of joining 4 tables together.

For a join on n tables, there could be n! left-deep trees and n! right-deep trees respectively. There could be even more bushy trees, etc. Given so many different join orders, it is important to find an optimal one among them. There are many different algorithms to find the optimal join order: exhaustive, greedy, randomized, transformation, dynamic programming (with pruning).

Join Reorderability

As illustrated in the last section, we have developed algorithms to find the optimal join order of queries. However, we could meet problems when we try to apply such algorithms on outer joins & anti-joins. This is because such joins do not have the same nice properties of commutativity and assocativitity associativity as inner joins.

Further, this means our algorithms cannot safely search on the entire space to find an optimal order (i.e. a significant subset of the search space is invalid). Such dilemma puts us into two questions: 1) which part of the search space is valid? 2) what can we do with the invalid part of the search space?

Up to now, hopefully the topic has become much clearer to you. In join reorderability, we are trying to figure out “the ability to manipulate the join query to a certain join order”.

Recent Researches

As follows, I summarize some recent researches on this topic and give my naive literature reviews on them.

Moerkotte, G., Fender, P., & Eich, M. (2013). On the correct and complete enumeration of the core search space. doi:10.1145/2463676.2465314

This paper begins by pointing out two major approaches (bottom-up dynamic programming & top-down memoization) to find optimal join order requires the considered search space to be valid. In other words, this probably only works when we consider inner joins only. Such algorithms could not work on outerjoins, antijoins, semijoins, groupjoins, etc.

To (partially) solve this problem, this paper presents 3 conflict detectors, CD-A, CD-B & CD-C (all correct, but only CD-C is also complete). It also shows 2 approaches (NEL/EEL & SES/TES) proposed in previous researches are buggy. The authors also propose a desired conflict detector to have the following properties:

- correct: no invalid plans will be included;

- complete: all valid plans will be generated;

- easy to understand and implement;

- flexible:

- null-tolerant: the predicates are not required to reject nulls (opposite to null-intolerant);

- complex: the predicates could reference more than 2 relations;

- extensible: extend the set of binary operators considered (by a table-driven approach).

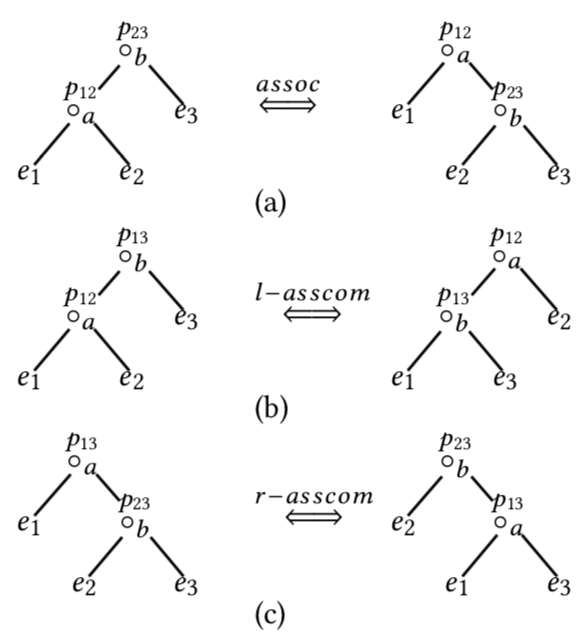

Then, the paper introduces the “core search space”, all valid ordering defined by a set of transformation rules. Notice that based on commutativity and assocativitity, the left & right asscom property is also proposed. A “conflict” means application of such transformations (4 kinds of transformations based on 4 properties: commutativity, associativity, l-asscom & r-asscom) will result in an invalid plan. “Conflict detector” basically tries to find out such “conflict”s.

If a predicate contained in binary operators do not reference tables from both operands, it is called a degenerate predicate. It is observed that for non-degenerate predicate:

- For left nesting tree: can apply either associativity or l-asscom (but not both); and

- For right nesting tree: can apply either associativity or r-asscom (but not both).

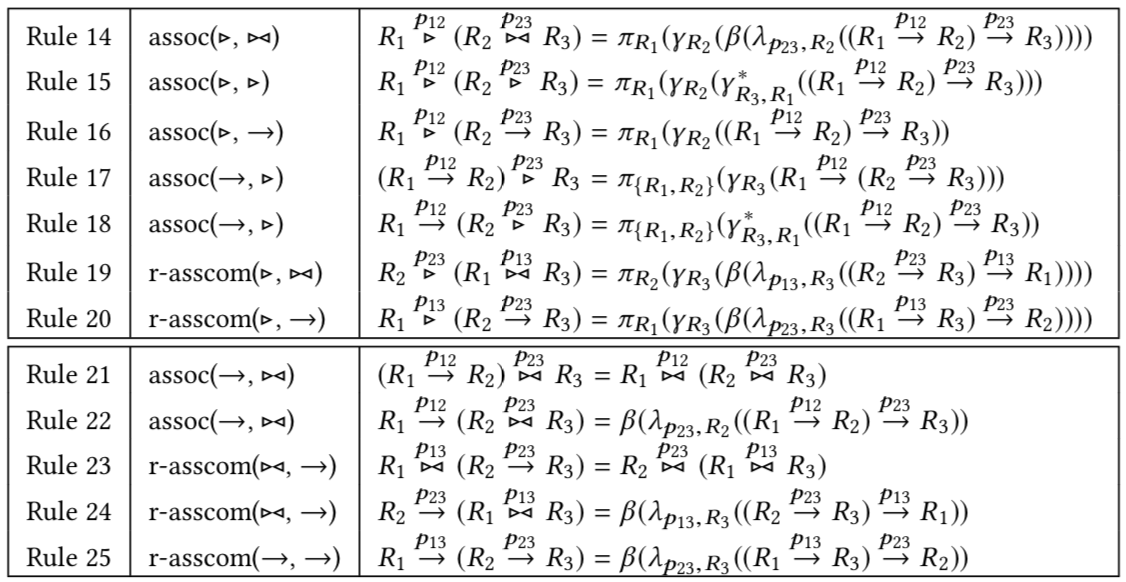

This observation in fact makes our life much easier. For either left or right nesting tree, we only need to consider one kind of transformation (rather than two kinds). We can further observe we usually at most need to apply commutativity once to each operator. We probably only need to apply associativity, l-asscom, or r-asscom less than once per operator as well. All valid & invalid transformations based on the 3 above properties are summarized in the following tables.

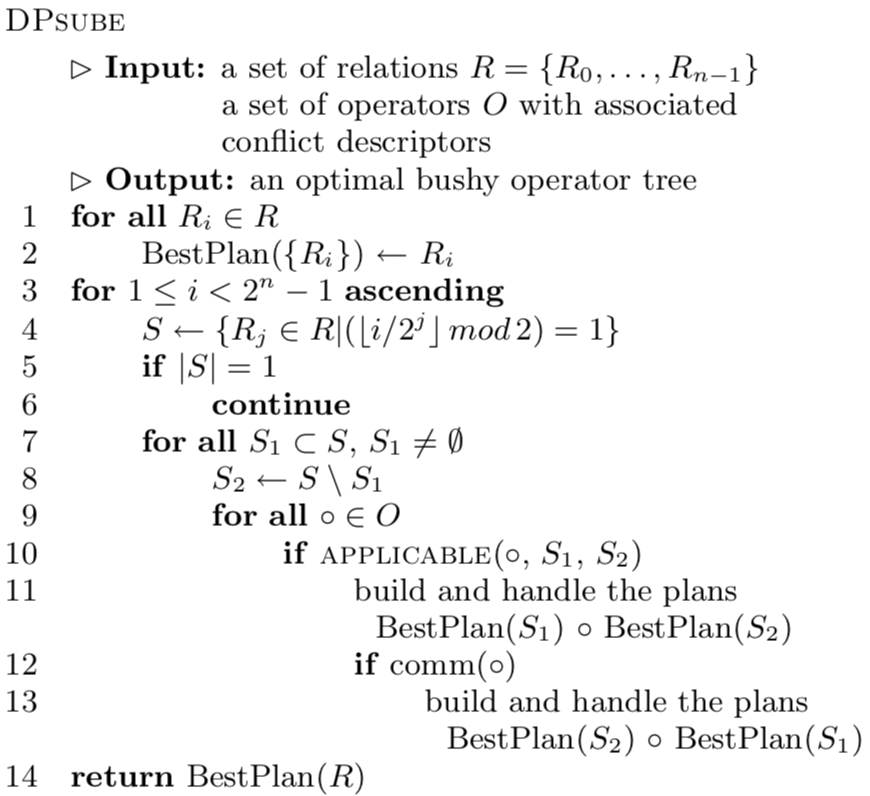

From this, we can infer that it is possible to create an algorithm to iterate through the whole search space in finite steps. Thereafter, the authors proposed an algorithm that extends the classical dynamic programming algorithm, as shown below.

Notice that the procedure above calls a sub-procedure Applicable, which tests whether a certain operator is applicable. Talking about “reorderability”, the rest would discuss how to implement this sub-procedure Applicable.

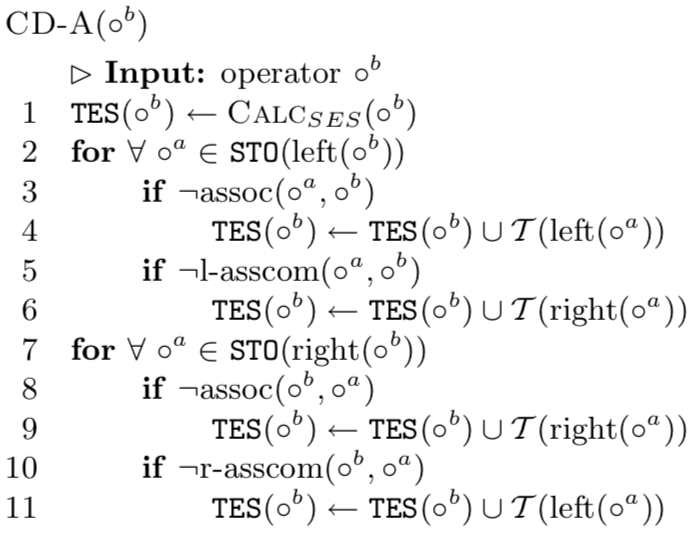

We introduce a few terms: syntactic eligibility sets (SES), total eligibility sets (TES). When commutativity does not hold, we want to prevent operators from both sides to communicate with each other. Thus, we further define L-TES and R-TES. By merging tables from either left or right operand, we can eliminate those invalid plans depending on whether l-asscom or r-asscom holds. This introduces the CD-A algorithm, as shown below.

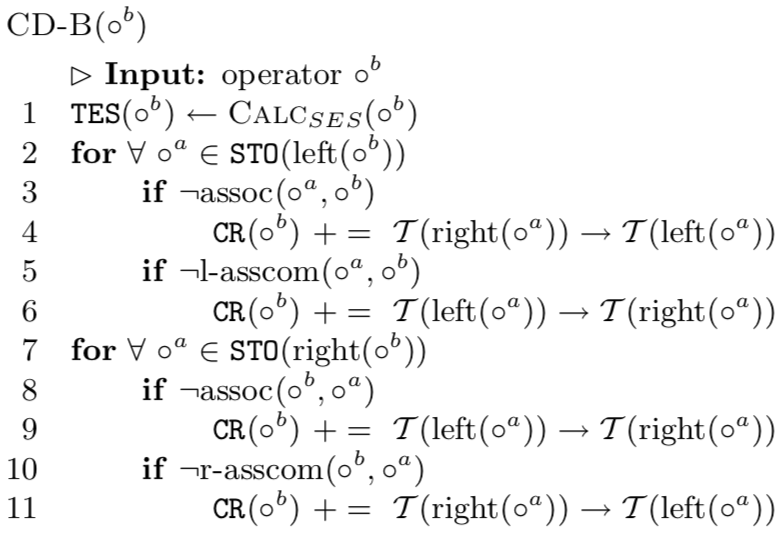

By introducing some conflict rules (CRs), CD-B is proposed as follows.

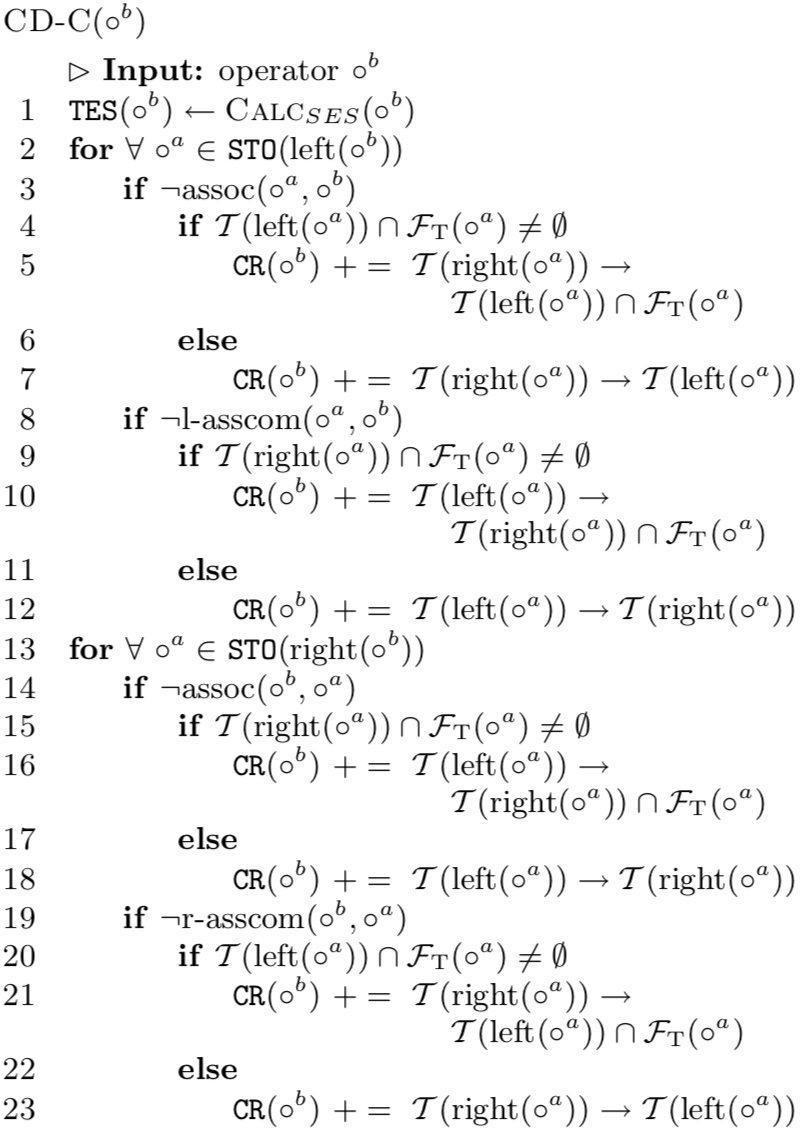

CD-C only improves the CRs.

Rao, J., Pirahesh, H., & Zuzarte, C. (2004). Canonical abstraction for outerjoin optimization. doi:10.1145/1007568.1007643

Similar to the previous paper, this paper also recognizes the difficulties in optimizing outerjoins due to the lack of commutativity and assocativitity. The authors believe that a canonical representation of inner joins would be the Cartesian products of all relations, followed by a sequence of selection operations, each applying a conjunct in the join predicates. So can we find a canonical abstraction for outerjoins as well? This outlines the objective of this work.

The two examples below goes with the following 3 tables, R, T and S.

| Table R | k | a | b | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Table S | k | a | b |

|---|---|---|---|

| s | 1 | 1 |

| Table T | k | a | c |

|---|---|---|---|

| N/A | - | - | - |

Example 1

1)

1 | S INNER JOIN T ON S.a = T.a |

will result in empty data.

2)

1 | R LEFT JOIN (1) ON R.b = S.b AND R.c = S.c |

will result in

| k | a | b | c | k | a | b | k | a | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Example 1 reordered

1)

1 | R LEFT JOIN S ON R.b = S.b |

will result in

| k | a | b | c | k | a | b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | 1 | 1 | 1 | s | 1 | 1 |

2)

1 | (1) INNER JOIN T S.a = T.a AND R.c = T.c |

will result in empty data.

Example 2

1)

1 | S LEFT JOIN JOIN T ON S.a = T.a |

will result in

| k | a | b | k | a | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

2)

1 | R LEFT JOIN (1) ON R.a = S.a |

will result in

| k | a | b | c | k | a | b | k | a | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | 1 | 1 | 1 | s | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

Example 2 reordered

1)

1 | R LEFT JOIN JOIN T ON R.a = T.a |

will result in

| k | a | b | k | a | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| s | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

2)

1 | (1) LEFT JOIN S ON R.a = S.a and T.a = S.a |

will result in

| k | a | b | c | k | a | b | k | a | c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | - | - | s | 1 | 1 | - | - | - |

Thus, we can see that the re-ordering of both R1 and R2 are invalid.

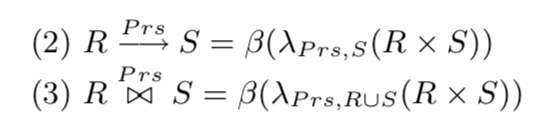

To solve the problem, this paper proposes a canonical abstraction for queries involving both inner and outer joins by 3 operators: outer Cartesian products × (conventional Cartesian products + if either operand is empty, perform an outer join so that the other side is fully preserved), nullification 𝞴 (for rows that don’t satisfy the nullification predicate P, set their nullified attributes a to null) and best match 𝞫 (a filter for rows in a table such that only those which are not dominated by other rows, and also not all-null themselves are left). Notice that such canonical abstraction would maintain both commutativity and transitivity, after which makes it much easier to find the optimal plan. This abstraction for left outerjoin and inner join is shown as follows.

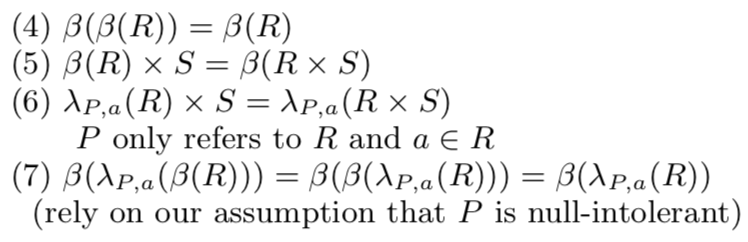

We can easily understand the rationale behind the relation above (we call this representation “bestmatch-nullification representation”, shortened as BNR). Let’s take the left outerjoin for an example. In a left outerjoin, the left operand is the preserving side while the right operand is the null-producing side. Thus, we have to nullify the right operand S with the predicate P (similarly, in an inner join, we need to nullify both operands). To prevent the results from containing spurious tuples, we further apply the best match operator. The image below summarizes some commutative rules for the two compensation operators.

Notice that although the nullification operator is not interchangable (commutativity), we can add another nullification operator to short-circuit the ripple effect and fix this.

TaiNing, W., & Chee-Yong, Chan. (2018). Improving Join Reorderability with Compensation Operators. doi:10.1145/3183713.3183731

This recent work extends the paper in 2004 by following a similar compensation-based approach (CBA) to solve the join reordering problem. In a simple query, all outerjoin predicates have only one conjunct, must be binary predicate referring to only 2 tables, no Cartesian product, and all predicates are null-intolerant. This paper also provides complete join reorderability for single-sided outerjoin, antijoins. For full outerjoin, the approach in this paper is better than previous work.

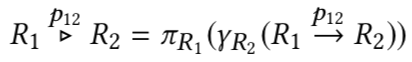

To formalize the notion of complete join reorderability, the join order is modelled as an unordered binary tree, with leaf nodes as the relations and internal nodes as the predicates & join operators. In this definition, the join ordering focuses on the order of all operands rather than the specific join operators used. In other words, to achieve a certain join order, we could possibly change the join operators used. Given a query class C and a set of compensation operators O, C is completely reorderable with respect to O if O can help every query Q in C to reorder to every possible order in JoinOrder(Q). Thus, this paper further purposes an Enhanced Compensation-based Approach (ECA), to enable reordering support for antijoins (by adding 2 more compensation operators). Specifically, antijoins are rewritten in the following way.

The above rule makes sense since the gamme operator basically removes those rows in R1 which could otherwise join with some row(s) from R2 (notice that a left antijoin basically means R1 - R1 left semijoin R2; and left semijoin means a projection to only include left operand attributes after a natural join). This two-step approach enables the pruning step to be postponed. The design of ECA has 4 desirable factors:

- The operators must be able to maximize the join reorderability;

- An efficient query plan enumeration algorithm;

- The number of compensation operators should be small;

- There exists efficient implementation to each compensation operator (both SQL level and system native level).

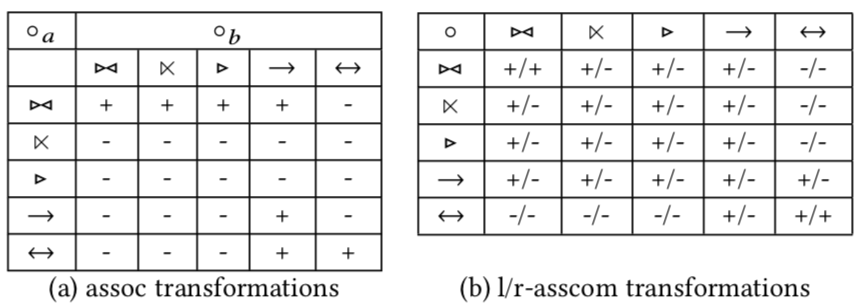

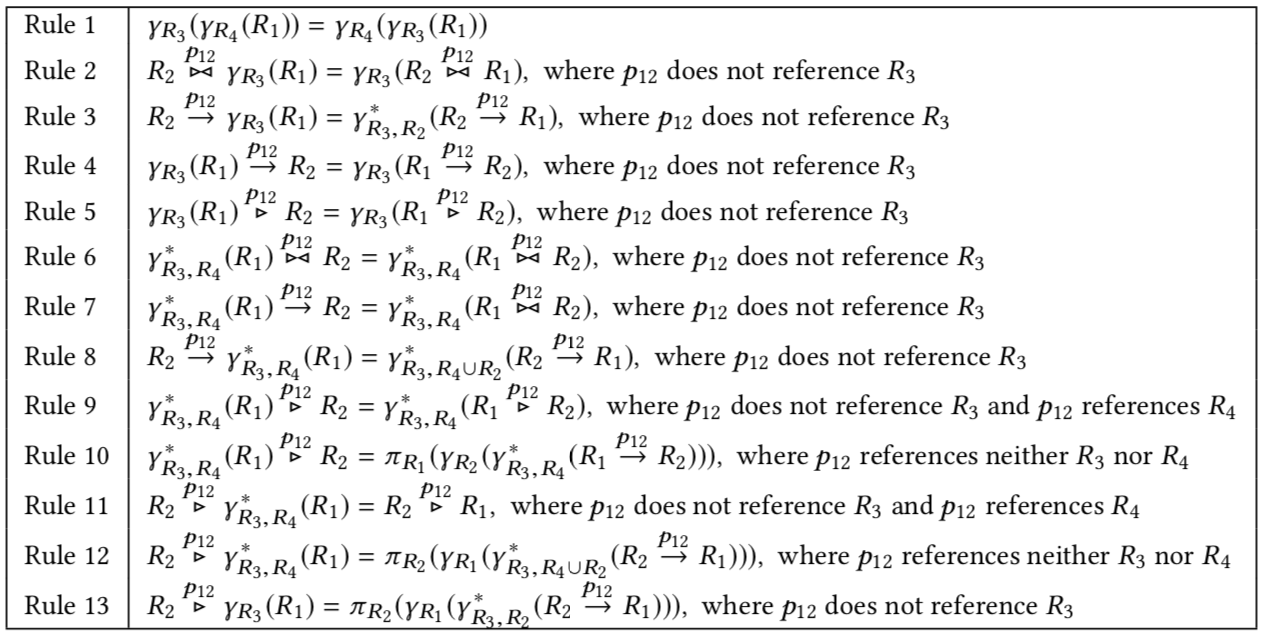

This paper introduces two new operators 𝞬 and 𝞬* . The first operator 𝞬 removes all tuples where the projection of a certain subset of attributes A is not null. The second operator 𝞬* modifies those tuples not selected by first operator by setting their attributes (excluding those in the subset of attributes to B) and then merge the two parts together. These two operators could be interchanged with conventional join operators as shown in the table below.

The above properties in fact lead to more rewriting rules as compared to the original CBA approach. The rules are shown in the table as follows.